For well over 5,000 years humans have been dyeing fabrics and advanced with the techniques for spinning and weaving. Plants such as madder, ford and bearberry were particularly prized for their bright colors. Over time, other plants became popular for their colors such as woad, saffron, kermes, mallow, turmeric, walnut and even juniper. The colors that they could produce ranged across the entire spectrum, although none were as vibrant as the synthetic dyes we use today.

Given such a long history, I was surprised to learn that Eco-dyeing was a relatively new invention in the 1990’s by an Australian textile artist India Flint. The act itself is so simplistic and produces such a lovely delicate pattern one would have thought it was one of the earliest methods. Perhaps, it was and there just isn’t enough evidence left for us to discern. It is also possible that there were others before India who were using the method, but they just did not popularize it as she did.

Eco-dyeing is very simple, as it combines two steps of the dyeing process into one. Rather than first boiling the plants to extract the dye and then adding the fabric to the boiling water to dye the fabric one seamless color, the extraction of the pigment and the application to the fabric is the same step. This produces the wonderful patterns of plants on the fabric to create a delicate web of colors and shapes. This process is known as a form of contact dye meaning the dye is transferred from the leaves directly to the fabric.

However, while it is very simple in concept, I still desired to try my hand at it under the tutelage of an expert. Additionally, the class doubled as a birthday gift to my mom as a mother-daughter outing. I signed us up at the PA Guild of Craftsmen which incidentally was celebrating 80 years of preserving the crafts. The guild serves to promote, educate, support and encourage the craftsmen of Pennsylvania. Through their work many artists have discovered their passions, developed their talents and made a living.

On an unusually warm October morning, we headed into the small city of Lancaster where the guild was located. As it was still fairly early the streets were still quiet which made finding parking in the garage a breeze. We took an easy stroll about a block to the location taking a note of the local eateries and shops for when the class had its break. There were instructions of how to enter the building before the Guild’s Shop opened which were easy to see and follow. Once we entered, there were lots of people who were helpful in pointing us up the stairs and down through the first room back to our classroom where we met Carol Reed, our wonderful and knowledgeable instructor.

Carol explained a short history of eco-dyeing and laid out the general flow of the class, first we would lay out the plants, then we would wrap them around the dowel, tie them neatly, plop them in some water, wait about 2 hours and then have the “Great Unveiling”. Carol explained that we would be using Eucalyptus which could produce a color of pinkish-orange akin to salmon, a softer pink, a lighter green or a darker almost purplish green. The color was affected by different things such as the age of the eucalyptus, how long the leaves were left to boil, how tightly the leaves were pressed into the fabric, how hot the water got and how much iron water was in the water. While this is a process that could use just plain water, the iron water helps the dye adhere to the fabric and gives it some added texture and depth.

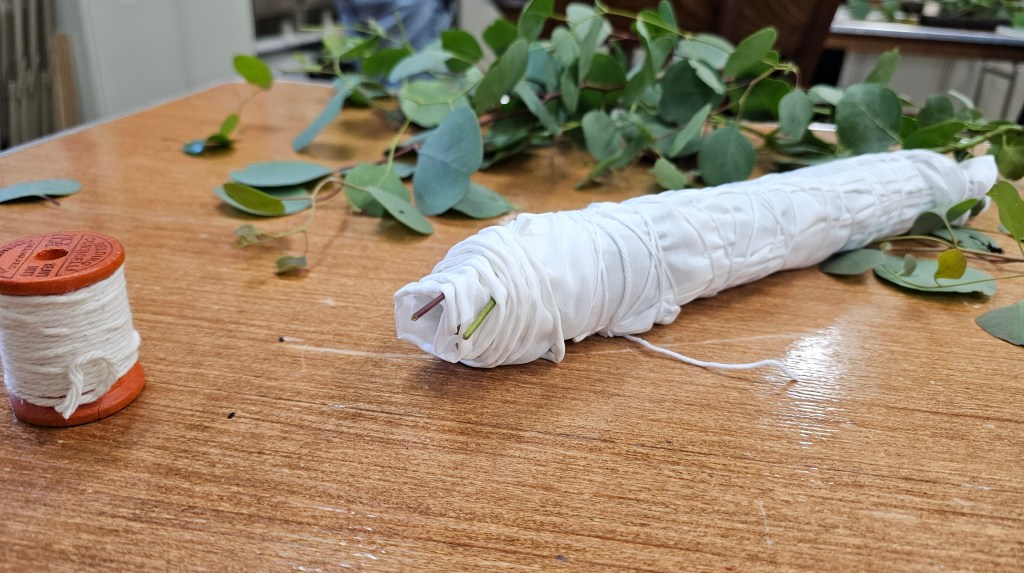

Utilizing her expertise, she was able to give us instructions to try and get the best results for what we desired. She explained that the outside pieces would be darker so if we wanted the darker section in the middle we should roll our scarves around the dowel in a different way. She told us which parts would transfer well, telling us that the very small, delicate leaves at the end would not transfer. She explained whether the way we were layering the leaves would end up looking lovely or like a weird blotch. She helped guide us as to when we had too many leaves or too few and how far out to go on the edges. She helped us wrap them with string and explained how the string patterns would turn up like small streaks on the outside edge.

I did not try to produce any sort of pattern, preferring to fully embrace the nature of the process as organic and natural. I cut down my long stems, having been advised that the stems would not roll well and then arranged the pieces across the scarf to mimic fallen branches and leaves scattered across the ground. I was careful not to add too many layers to avoid having ugly blotches on my scarf. I paid heed to the adage that less was more, knowing that the scarf would be folded over so the dye would be layered over the scarf. With the help of my mother I carefully wound the fabric tightly around the dowel as Carol had explained that the better the contact, the better the dye would be. I tied the string taut around the bundle securing the whole thing and then made a note of what mine looked like since Carol warned us not to put our bundles in until we could compare to discern whose was whose.

Once everyone had their bundles ready we put them in their designated pots and took a break since we would need to wait close to an hour and a half for the dye to really seep out of the leaves and onto the fabric. We were advised eucalyptus was a particularly hardly leaf which required a longer dyeing time. Carol told us that we could use a myriad of other plants for the same process, but we would find that much less time would be needed. We were also advised that if we did leave more delicate plants in that they would turn to mush and be much more difficult to get off the fabric when the dying process was over. Carol shared that the eucalyptus leaves would just fall off, but other leaves she usually has to carefully remove.

Having previously scouted out the area on our way in, my mom and I made our way just across the street to the Onion Cafe. It was a curious blend of American and Korean food where bowls of Ramen were offered beside burgers and fries. There were one or two “fusion” items mostly consisting of the addition of kimchi to the American options. However, as I was feeling a little

under the weather, I opted for a spicy Ramen, figuring a hot, spicy soup was the perfect panacea for what might be ailing me. My intuition was correct, as the Ramen was perfect and I felt much better afterwards.

We then strolled through the shops. Our favorite was a vintage clothing store,that was sadly going out of business. However, this meant they were running a clearance sale resulting in some steep discounts on our purchases, two hats (one bonus hat pin), a pair of fingerless gloves and a linen top. We then headed back to the guild for the “grand reveal”.

To say that I was delighted by the outcome is an understatement. I absolutely loved how my scarf turned out. Mine had transformed into soft, delicate pinks, mixed with light green hues which gradually turned into darker greens and purples. The leaves scattered across the fabric had left the impression of a field or forest of plants. The rest of the group oo’d and aw’d when they first saw it as mine was the first to be unwrapped. The others went shortly after. Despite having followed the same process, boiling in the same pots, the results ran the gambit of colors and patterns. It was so interesting and even Carol couldn’t quite explain why one person’s turned out to be a vibrant orange and another person’s stayed almost completely green.

We were told to rinse our scarves out until the water ran clear and allow them to cure for a few days before washing or wearing them to allow the color to fully set. We were told that the colors may brighten as it dried. We thanked our instructor, packed up the scarves in small plastic bags and headed home with our prizes.

I think what I really enjoyed about the whole process was how natural it all way from the silk fabric to the dye that only came from the leaves of the plant, to the patterns that were transferred to the fabric to even the simple ingredients of water and iron water (made from rusted nails, water and vinegar).

We are so disconnected from the process of what we wear and often what we wear is synthetic which utilizes process that are harmful to our environment and ultimately ourselves. This was a way to really connect to a tradition that, as I said, goes back thousands of years, even if it’s using a very modern technique. It was simple and elegant leading to beautiful results.

How can you make your own eco-dyed scarf?

You can, like me, find a class nearby which offers a lesson in the technique which not only teaches you the basics but also gives you access to an expert to help guide you in learning the smaller nuances of the craft. I find such experiences worthwhile and helps to enhance any first endeavor into a craft. I also like supporting local artisans, by helping them I continue to have access to specially made objects which enrich my life and my home. My local economy improves and I help preserve this precious piece of human culture for the future.

However, not everyone has access to craftsmen and women. However, these sorts of classes are increasing in popularity as many people are realizing that they’ve lost something by going completely digital. They want to feel physical objects, interact with their environment and embrace life. Plus studies have shown that engaging in activities of creation is good for our mental wellbeing, it reminds us that we aren’t helpless and capable of great things.

Still, you may find, dear reader, that you are unable to locate an instructor for your dyeing needs. Do not despair, as I have told you the principles of the task are quite simple and through some experimentation you are surely to get results you are happy with. I will say that it is recommended not to use the same pot for dyeing as you do for cooking. Luckily cheap pots can be found at a local thrift store. Silk scarves can be found at dharmatrading.com and the eucalyptus can be found at your local flower shop or even some chain grocery stores. Iron water is easily made with some rusty nails, water and vinegar and you’re off! More explicit instructions can of course be found online.

You may find that you truly enjoy the process of making eco-dyed fabrics and a new hobby as been discovered. I will say the temptation to make more is certainly there, but I shalln’t give in to the temptation as I don’t know that I have space in my life right now for another hobby. Mostly my storage spades for the supplies. Perhaps one day, dear reader.

Completed: October 2024

Cost: $80 for the class (materials cost included)

Miles from home: 12